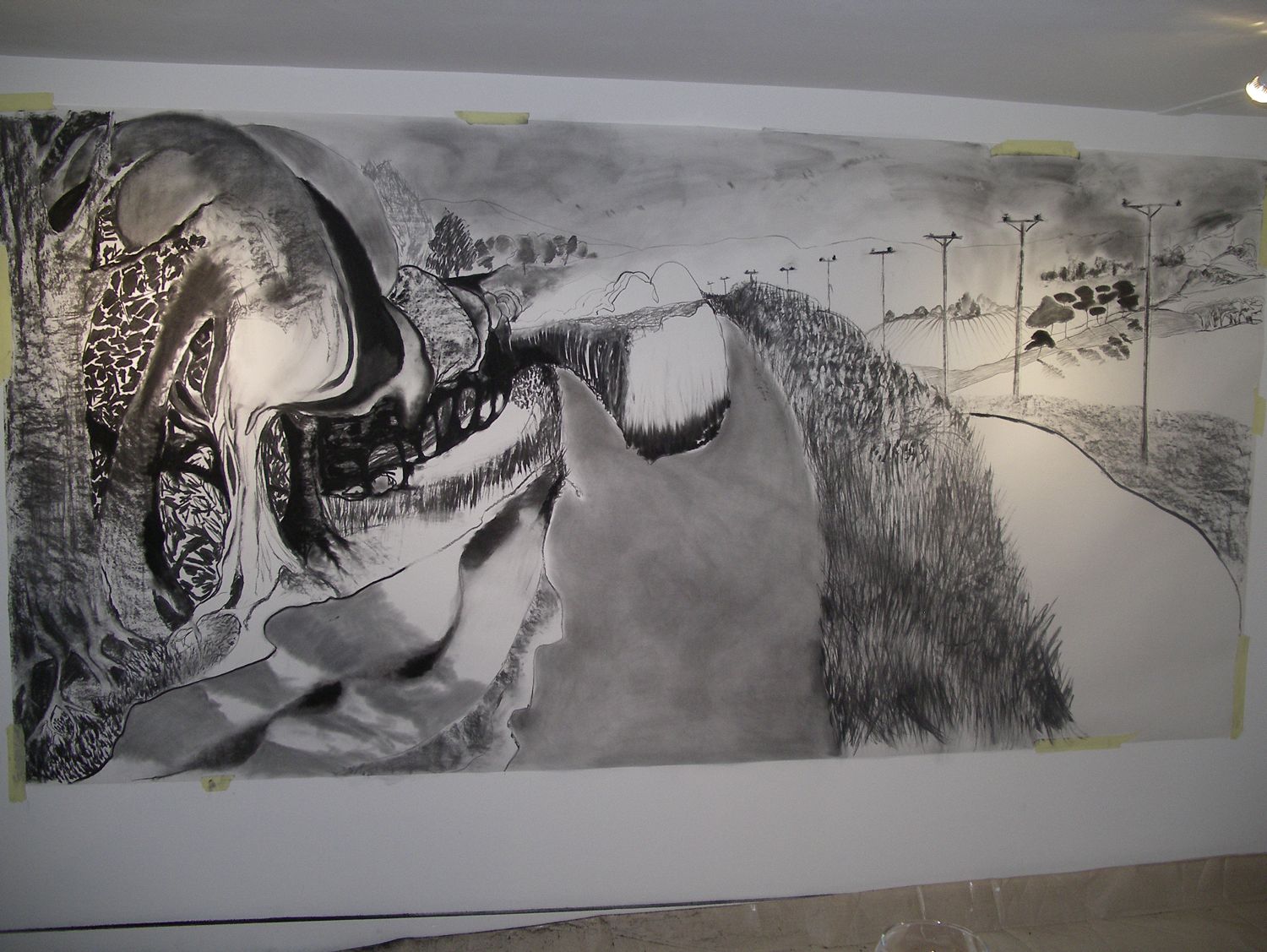

I spent a marvelous day with environmental artist Pete Ward who led a small group of artists ( Duncan Hopkins, Francesca Owen, Rachel Ara and Geoff Mead ) in search of pigments in the earth around North Devon. Almost every known mineral and pigment has at some time been found in this area (from north Devon to Exmoor). These are the colours of ancient artists and they are still in the ground around us. Pete has been working with these locally found pigments for many years. His paintings, made with the materials he brings back to the studio, are not only stunning to look at they touch something deep down, like a forgotten memory reawakened. Other works are made in situ, ephemeral interventions on land that tread lightly, echoing the marks made by the passages of time, people, animals, forces of nature and beauty around us.

After a day spent with Peter I cannot look at rocks or mud in the same way; rocks need to sucked to see if they yield (mudstone will dissolve in the mouth) because mud is a material for art.

It has been said that artists remind us of what we have lost, and this is certainly true of Peter Ward. He connects us to the very beginning: to the beginning of the earth, to the beginning of art and to the beginning of life.” Sandy Brown, Resurgence magazine. BIDEFORD BLACK [1] is a unique, naturally occurring carbon based mineral, or culm deposit, running alongside seams of high quality anthracite (coal) across North Devon. The deposits were formed over 350 million years ago. According to research, conducted by local geologist Chris Cornford, the mineral is unique in that it only contains the lignum of tree ferns rather than the spores, bark and leaf matter normally associated with coal deposits where the outer layers were removed before being deposited and trapped beneath layers of landslip soil and rock. The deposits were crushed and pushed 8km beneath the earth’s surface as plate tectonics ground and compressed the fine vegetable matter to form the greasy clay deposits we find today. The mineral is made up of flat hexagonal platelets, similar to that of graphite. This structure may have been exaggerated by the shearing and sluicing action of the earth. The mineral consists of roughly equal parts of carbon, silica and alumina – the carbon providing the exceptionally rich black colouration that made it so useful as a pigment. The seams stretch from Hartland and Abbotsham on the coast in a southeasterly direction beneath Bideford and inland as far as Umberleigh. ‘Mineral Black’, or ‘Biddiblack’ as it was also known, was mined for 200 years in Bideford, processed and used commercially as a paint and dye until 1968 when cheaper oil-based pigments became available. As an artists pigment it was sold in the eighteenth century by companies such as Reeves of London who also sold raw umber from Combe Martin and ochre from East Down in their paint boxes. Pete Ward is currently leading a research project on the history and use of Bideford Black as an art material.

[1] http://www.bidefordblackblog.blogspot.co.uk